“You can’t handle the truth”: What HMRC’s TBML Handbook reveals about risk assessments

There’s a moment in A Few Good Men that every compliance professional should secretly love.

Lieutenant Daniel Kaffee (Tom Cruise), hungry for justice, shouts across the courtroom:

“I want the truth!”

Colonel Nathan Jessep (Jack Nicholson), icily composed, fires back:

“You can’t handle the truth.”

That line has become cliché in popular culture, but in financial crime risk management, it’s uncomfortably accurate.

As an industry, we keep saying we want to be intelligence-led.

We want to base our risk assessments on “real-world threats.”

We want the truth.

But when the truth actually arrives, in the form of detailed intelligence like HMRC’s Trade-Based Money Laundering (TBML) Handbook, most institutions can’t handle it.

Not because they don’t want to, but because their methodologies were never built to.The conventional Business-Wide Risk Assessment (BWRA) remains a procedural courtroom, obsessed with evidence, but constrained by the wrong rules of evidence. It catalogues risk factors (jurisdictions, customers, products) as if reading out a charge sheet, yet never cross-examines the behavioural evidence that shows how those risks actually manifest.

When you look closely, it’s clear: the industry isn’t short of intelligence; it’s short of a framework that can hear evidence.

The intelligence is there, the witnesses are ready, but the framework can’t call them to the stand.

And that’s what the TBML handbook exposes. It’s more than a typology guide; it is a stress test for the industry’s ability to ingest intelligence.

Because a firm that can’t structure what HMRC has just given us can’t credibly claim to be risk-based — or intelligence-led.

The Illusion of Intelligence-Led Assessment

Let’s start with the uncomfortable truth.

When regulators call for a “risk-based approach informed by intelligence,” most firms nod gravely and update a sentence in their methodology documents. But their BWRA templates, whether Excel grids or consultancy-built dashboards, remain static.

They are designed to record risks, not interpret them.

They categorise by risk factor (“customer risk,” “geographic risk,” “product risk”) and assign scores based on high-level descriptors, such as “complex ownership structure” or “high-risk jurisdiction.”

The result is an assessment that may feel quantitative, but is conceptually shallow: it captures what is risky but not why or how.

So, when a genuinely rich intelligence product like HMRC’s TBML handbook lands — with detailed behavioural patterns, threat vectors, and process vulnerabilities — there is nowhere for it to go.

The BWRA’s design language is simply incompatible with the information it’s being asked to digest.

Why traditional BWRAs fail to absorb intelligence

Most current BWRAs fail for three structural reasons:

(i) They lack a mechanism to represent threat behaviour

Traditional BWRAs are organised around risk factors, not risk events.

They can tell you that trade finance is a “high-risk product,” but not what actually happens when that risk materialises.

So, when HMRC describes a scenario where criminals over-invoice shipments, re-route goods through intermediaries, and settle payments from unrelated third parties, there’s nowhere to put that information. The model can’t capture behaviour.

(ii) They have no linkage between external threats and internal exposure

Even if you wanted to reflect that HMRC has identified TBML as a priority threat, you can’t link it to your own business profile. The BWRA framework doesn’t provide a data structure that says, “Here is a typology; here is where, and to what extent, it’s relevant in our organisation.”

It might appear in narrative text, but it never shapes the scoring, prioritisation, or control evaluation.

(iii) They treat controls as static and generic

Most BWRAs evaluate controls in broad categories, “KYC,” “transaction monitoring,” “training.” These are compliance labels, not control mechanisms. They don’t differentiate between a control that addresses TBML and one that tackles insider fraud.

So even when intelligence identifies precise control weaknesses (say, invoice-value verification or monitoring for circular trade routes) there’s no granularity in the control library to reflect that.

In short: traditional BWRAs can acknowledge intelligence, but they can’t ingest it.

The TBML handbook as a stress test

Let’s put that to the test.

Imagine you’re an MLRO reading HMRC’s handbook. You know it’s relevant. You can see how the typologies map to your trade-finance or payments operations. But when you sit down to update your BWRA, what happens?

At best, you add a line under “Product Risk – Trade Finance (High)” with a note referencing the HMRC guidance. Maybe you tweak a score.

That is not intelligence-led risk management. Reinforcing one of our earlier criticisms, that is compliance theatre.

The handbook is rich in behavioural insight, how value is obscured, how documentation is falsified, how legitimate trade flows are manipulated. But unless your BWRA has a mechanism to express those behaviours, the insight evaporates. It never reaches the part of the organisation responsible for designing or calibrating controls.

How an intelligence-ready BWRA works

Our enhanced methodology was designed precisely to solve that problem. It assumes that external intelligence (from HMRC, FATF, NCA, or enforcement cases) is a continuous input, not an afterthought.

Let’s use the TBML handbook as a live example.

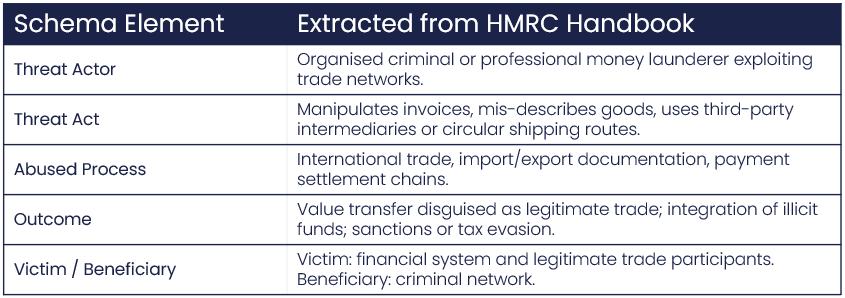

Step 1: Ingest as a Risk Event

Rather than forcing “TBML” into a risk-factor box, we define it as a risk event, the basic analytical unit of our framework.

Resulting Risk Event:

“Criminals exploit trade transactions and documentation to disguise the movement of illicit value through legitimate import and export channels.”

Each event becomes a discrete unit within the BWRA, linked to specific products, geographies, and customer types. It can be rated for inherent and residual risk, updated dynamically as new intelligence emerges.

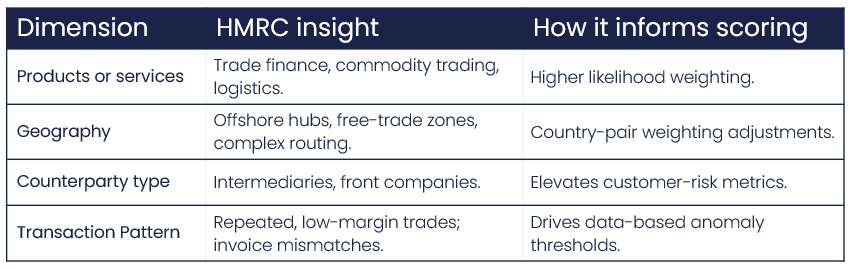

Step 2: Map to the Business Profile

Next, we test the risk event against the business profile, the data describing how and where the organisation actually operates.

Here, HMRC’s insights translate directly into measurable exposure indicators:

This converts qualitative intelligence into quantitative exposure modelling, the evidence base for defensible likelihood ratings.

Step 3: Link to Control Design

Finally, we connect the event and exposure to our control typology, framing whether they are preventive, detective, corrective or directive.

Every control is traceable back to a threat behaviour, creating regulatory defensibility, and a clear audit trail from intelligence → risk → control.

But that’s not the end of the process.

Because even the most sophisticated control framework leaves something behind, the part of the threat that remains live, unmanaged, or imperfectly mitigated.

And that’s where traditional methodologies stumble again.

They stop at control coverage and call it “residual risk,” reducing the concept to a mathematical afterthought, inherent score minus control score.

A genuinely intelligence-driven framework goes further. It asks: What behaviours are still active? What risks remain visible, and acceptable, after the controls have done their work?

That question takes us to the next layer: residual risk and its alignment to risk appetite.

From Residual Risk to Risk Appetite

This brings us to the concept many firms struggle with most, residual risk, and the subject of last week’s reflection on the “Emperor’s New Clothes” of risk appetite statements.

In most institutions, residual risk is little more than aggregated arithmetic, an inherent risk score minus a control score. It tells us nothing about what remains unmanaged, or how that remainder aligns to stated appetite.

That is because the traditional BWRA doesn’t measure risk in behavioural terms. It can’t say which threat mechanisms remain active after controls are applied, it only knows that “some risk remains.”

In our framework, residual risk is tangible.

Once you define the risk event (behaviour) and the controls (responses), residual risk represents the unmitigated behaviours that still pose exposure. For TBML, that might mean:

Residual exposure to under-invoicing where trade-data benchmarks are unavailable;

Remaining vulnerability to circular trade flows routed through non-transparent intermediaries;

Unaddressed gaps in monitoring logic for complex multi-jurisdiction chains.

Those specifics are what allow you to discuss risk appetite credibly.

Instead of abstract statements (“We have no appetite for money laundering risk”) you can define appetite in measurable behavioural terms:

“ Our appetite does not extend to trade flows we cannot see or substantiate.”

That statement is not rhetorical; it is operational. It defines a measurable boundary based on visibility and verification, a standard that can be tested, evidenced, and managed.

This closes the loop. Intelligence informs events; events define exposures; exposures test controls; and what’s left defines residual risk, the part that must sit within (or beyond) appetite.

Only then does risk appetite move from aspiration to application, from words on a page to a working measure of confidence in what remains.

From static to adaptive

The exercise above illustrates the transformation from a static compliance artefact to a dynamic intelligence system.

Each new external insight can be parsed through three questions:

→ Does this describe a new risk event?

→ Does it change our exposure profile?

→ Does it require us to alter our control design or residual risk?

That’s what “risk-based” should mean.

Not filling boxes, but continuously recalibrating our understanding of risk relative to real-world behaviour and stated appetite.

Closing thought

HMRC’s TBML handbook shouldn’t be another PDF on a shared drive. It should be a live data feed into the risk engine of the firm.

That most BWRAs can’t accommodate that tells us less about the handbook and more about the architecture of our frameworks.

Because the problem isn’t a lack of intelligence, it is the inability to structure it.

Our goal is to change that:

To move from compliance theatre to behavioural insight,

From static matrices to dynamic learning,

And from hollow appetite statements to measurable confidence in what remains.